Battera kombu plays an essential role in the flavor and quality of battera sushi, a classic mackerel sushi dish from Osaka. By covering saba-zushi (mackerel sushi) with kombu, a distinctive effect is created: the soft, rounded flavor of the kombu enhances the umami of the fish, giving the dish greater depth and balance overall. The umami of the kombu slowly permeates the sushi, resulting in a milder, more rounded taste. In short, battera sushi is Osaka’s version of saba-zushi: pressed mackerel sushi traditionally topped with kombu to deepen its flavor.

Battera sushi is a form of hakozushi (pressed sushi made in a wooden mold), traditionally topped with marinated mackerel and covered with a thin layer of kombu. In Osaka, this style of sushi was historically more popular than nigiri and was often purchased as takeout or as a convenient lunch on the go, for example when heading to the theater. Battera is widely regarded as the representative mackerel sushi of Osaka.

In this context, the kombu does not merely serve as a protective layer to prevent drying, but acts as an active carrier of flavor. These battera kombu sheets (6,5 x 19 cm) from Goda Shoten are specifically developed for this purpose and are used by sushi chefs in Osaka and beyond. In short, this is a truly unique, high-quality product.

Origin of the kombu: the highest quality

The base of this battera kombu is ma-kombu from Shirakuchi-hama, located in southern Hokkaido (Dōnan). This area is renowned for kombu with a high umami content.

Ma-kombu is divided into three production areas:

- Shirakuchi-hama

- Kurokuchi-hama

- Honba-ori-hama

Of these three, Shirakuchi-hama is considered the highest quality. Historically, kombu from this area was presented to the imperial court and the shogunate, earning it the name kenjō-kombu (tribute kombu). This kombu produces a clear, refined dashi and is highly prized by chefs.

At Goda Shoten, this ma-kombu is fully utilized. During processing, several different products are created, each with its own application:

- Oboro-kombu

Shaved paper-thin by hand. Used for dishes such as kobu udon and as an elegant topping. Extremely soft and light in texture.

- Tororo-kombu

Shaved into soft, fibrous strands. Used to add extra depth and umami to rice and noodle dishes.

- Shiroita-kombu (--> battera kombu)

The core portion that remains after oboro and tororo kombu are shaved is called shiroita kombu. Shiroita kombu is also used decoratively, for example on kagami mochi during the New Year. The sheets sold here, however, are specifically cut (not shaved) into thin, rectangular sheets for use on battera sushi.

This battera kombu is firm enough to hold its shape, yet gradually absorbs and releases flavor during marination and resting, subtly enhancing the sushi.

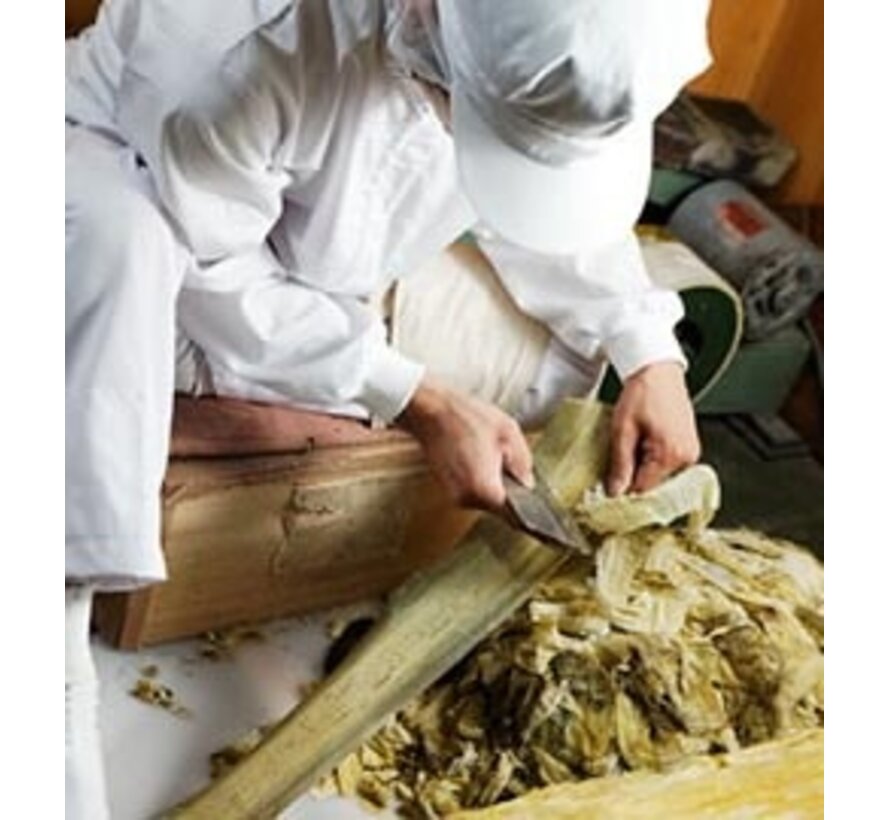

Knife techniques and hand processing: centuries-old craftsmanship

As early as the Edo period, kombu from Hokkaido was transported to Osaka by trading ships. This made kombu a cornerstone of the food culture of Kamigata (the region around Osaka and Kyoto). As kombu came into wider use, various processed products such as tsukudani and vinegar-marinated kombu emerged.

The city of Sakai, near Osaka, developed into a unique center for kombu processing thanks to its centuries-old tradition of knife-making and metalworking. It was here that the artisanal technique of hand-shaving kombu was refined, leading to products such as oboro kombu, tororo kombu, and battera kombu.

During its peak period (from the Taishō era to early Shōwa), Sakai had as many as 140 to 150 kombu processors. Today, only a handful remain: within the Sakai Kombu Processing Cooperative, just 11 companies are still active, and only four—including Goda Shoten—continue to process kombu entirely by hand. The number of skilled artisans has declined to around ten.

Hand-shaving kombu requires specialized knives and exceptional skill. The knives used for oboro kombu first undergo a process in which the blade edge is slightly curved; this technique is known as akita. The result is a knife that is not only extraordinarily sharp, but also flexible and resilient, allowing it to almost cling to the kombu as it is shaved.

This technique is made possible by Sakai’s 600-year-old knife-making tradition. The craftsmen at Goda Shoten wield these knives as an extension of their own hands. During shaving, they must also ensure that the surface of the shiroita kombu remains completely intact, as this core will later be used for battera sushi.

Goda Shoten is one of the oldest kombu processors still active in Sakai and has been hand-processing kombu for over 70 years. In a city renowned for its craftsmanship—from knives and incense to textiles and wagashi—hand-shaved kombu remains a quiet yet essential tradition.

Everything begins in Sakai: the knives, the artisans, and the techniques that come together in a product indispensable to Osaka’s sushi culture.