Matcha: the green tea powder that has become immensely popular in recent years, especially in the form of a latte. Traditionally, however, matcha has been enjoyed in Japan for centuries as “real tea” — without milk. Matcha is far more than just a trend. Behind this beautiful green powder lies a long and rich cultural history. We warmly invite you to explore it with us.

Green tea (ocha) is — together with sake — Japan’s national drink. Tea reached Japan from China around the eighth century. In its early days, tea was mainly regarded as a medicinal beverage and a stimulant for the upper classes. Today, tea is much more than a simple drink in Japan: it is deeply connected to ritual, Zen philosophy, and everyday life. Over the centuries, many rules and forms of etiquette have developed, all of which are now deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

Japanese tea is green because the tea leaves are steamed immediately after harvesting. This process destroys the enzyme that would otherwise cause the leaves to ferment and turn black. In Japan, there are two main types of tea: leaf tea and powdered tea (matcha). For matcha, the leaves are dried flat and later ground into a fine, light-green powder. Matcha is the drink of the Japanese tea ceremony and is prepared per serving, not by the pot.

Traditionally, matcha consists of nothing more than water and tea powder whisked together. Before a Japanese tea ceremony, a sweet is often eaten — such as mochi filled with red bean paste (anko) — to complement the slightly dry and bitter taste of the tea. Sweets may also be served alongside the tea. Many Japanese confections have been specifically developed to be enjoyed with green tea.

Matcha is not only consumed as a drink, but is also used in a variety of dishes. For example, it is incorporated into variations of sweet potato and chestnut purée (satsuma-imo kinton), a popular New Year’s dish. Matcha can also be mixed with syrup and poured over a pyramid of shaved ice.

Today, matcha is enjoyed all over the world — and also in Japan (especially in larger cities) — in the form of lattes (sometimes with fruit purée), and it is used in countless culinary applications. Think of matcha tiramisu, cakes, cookies, mochi, and more.

Despite its popularity, matcha is not always easy to enjoy right away. Preparing it requires some practice and the right techniques, and finding the right amount of powder (and any additional ingredients) takes a bit of experimentation. Matcha naturally has a light bitterness, umami, and a fresh, almost grassy aroma. Although subtle, this can take some getting used to — much like coffee does for many people. Give yourself the time to taste and experiment; when you do, matcha can become a truly wonderful experience.

Matcha is also often consumed as an alternative to coffee, as it can provide a pleasant energy boost thanks to its caffeine content.

Why we chose this matcha

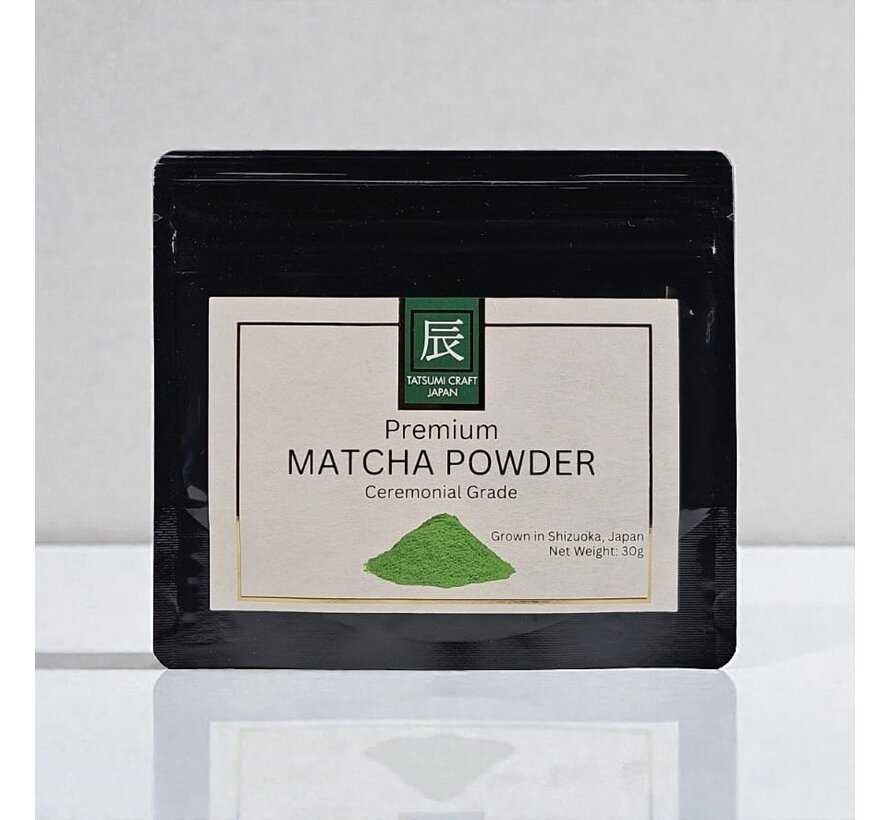

At a time when matcha is everywhere — in countless forms, qualities, and price ranges — it can be difficult to know where to look. We want to offer clarity and calm. That’s why we currently offer just one matcha: high quality (first harvest) at a fair price. This matcha is delicious to drink pure, but also perfect for lattes (hot or iced).

You sometimes hear that lower-quality matcha is better for lattes, but we disagree. Even in a latte, you want good matcha — just like with coffee and milk.

The quality of our matcha is significantly higher than so-called “culinary grade,” which is intended mainly for cooking and baking and is often cheaper and processed differently. That said, our matcha can absolutely be used in recipes such as cakes or cookies, where it brings out a rich, full matcha flavor and turns something simple into something special. Because we wanted a matcha that shines both on its own and in (warm) lattes, we especially value its vibrant kick and beautiful umami.

Origin and production

Our matcha is a blend sourced from several contracted farms within the same region: Shizuoka, Japan. Using leaves from multiple farms (rather than a single one) does not necessarily mean lower quality — but it does make the matcha more affordable.

Our producer grinds the tencha (tea leaves) into matcha using a fine mill and a low-temperature method. The tea plants from which the tencha leaves are harvested are shaded before picking — a traditional shading technique that is essential for producing true tencha (碾茶).

Our matcha is made from the first harvest. These younger leaves result in higher quality. Historically, “ceremonial grade” refers to the highest-quality first-harvest leaves used in the traditional Japanese tea ceremony (Chanoyu). While the term is now sometimes used for marketing purposes to distinguish matcha from culinary grades, at its core it refers to matcha with deep umami, a velvety texture, and suitability for drinking pure.

Flavor and aroma

Our matcha offers a beautiful balance of softness and richness, with deep umami, natural sweetness, and a light bitterness. It is a matcha with a kick: the umami is pronounced and remains present even in a warm latte (which often slightly mutes matcha’s flavor). The aroma is fresh and delicate, with a clean, grassy note. Of course, taste is always subjective.

Don’t be misled by claims that matcha should not be bitter at all. Matcha does have a characteristic light bitterness — and that is precisely why it has been loved for centuries. Excessive bitterness, however, especially when combined with a “fishy” taste or smell, is not desirable. In such cases, the quality of the powder may be lower, but it can also be caused by using too much powder or water that is too hot.

Storage

Always store matcha airtight, in a dark and cool place. Oxygen, light, and heat cause matcha to fade quickly and lose flavor. After opening, matcha is best enjoyed within 4–8 weeks, though this does not mean it becomes unsafe or unpleasant afterward. When resealing the bag, gently press out all the air (careful not to spill the powder!) and make sure the seal is fully closed. Moisture should never come into contact with the powder, so ensure your spoon is completely dry before use.

The inner pouch containing our matcha is laminated and UV-resistant to keep the powder optimally fresh. Matcha’s best-before date is relatively short, mainly because quality can slowly decline — not because the product spoils quickly. Unopened matcha often remains good for months. The best-before date is usually no more than one year after the first harvest, to ensure optimal flavor and quality.

Over time, color, taste, and aroma may diminish, but this does not necessarily mean the product has gone bad. Always smell, look, and taste: if everything seems normal, there is usually no issue. Matcha is also intentionally sold in small quantities (like our 30 g), making it likely you’ll finish it well before the best-before date.

Tips for making a great matcha

- Sift the powder before whisking to prevent clumps (which are truly unpleasant). Make sure the sieve is completely dry.

- Use water at a maximum of 80°C (176°F). Hotter water can burn the matcha and make it very bitter. Ideally, use boiled water cooled to 80°C or heat your water directly to that temperature.

- Take good care of your chasen (bamboo whisk):

- Wet the whisk before use (up to just below the string).

Soak it for 1–2 minutes in warm water (50–60°C) so the bamboo fibers soften and wear less quickly, and so the green color doesn’t immediately stain the bamboo.

Whisk in zigzag motions (W or M shape) — do not stir in circles.

Whisk quickly but without pressing hard. Foam is created by speed, not force. Touch the bottom of the bowl as little as possible to prevent wear.

Rinse immediately with lukewarm water, without soap.

Let dry on a whisk holder (kusenaoshi), in a well-ventilated place away from direct sunlight.

Replace your chasen when the tips break or when it no longer creates good foam.

- Never put your tools in the dishwasher.

- Weighing your matcha can be helpful: it ensures consistency and helps you find your ideal ratio. Too much matcha can lead to bitterness, an overly strong mouthfeel, or a gritty texture — and matcha contains quite a bit of caffeine. Note: regular kitchen scales are often not precise enough for such small amounts.

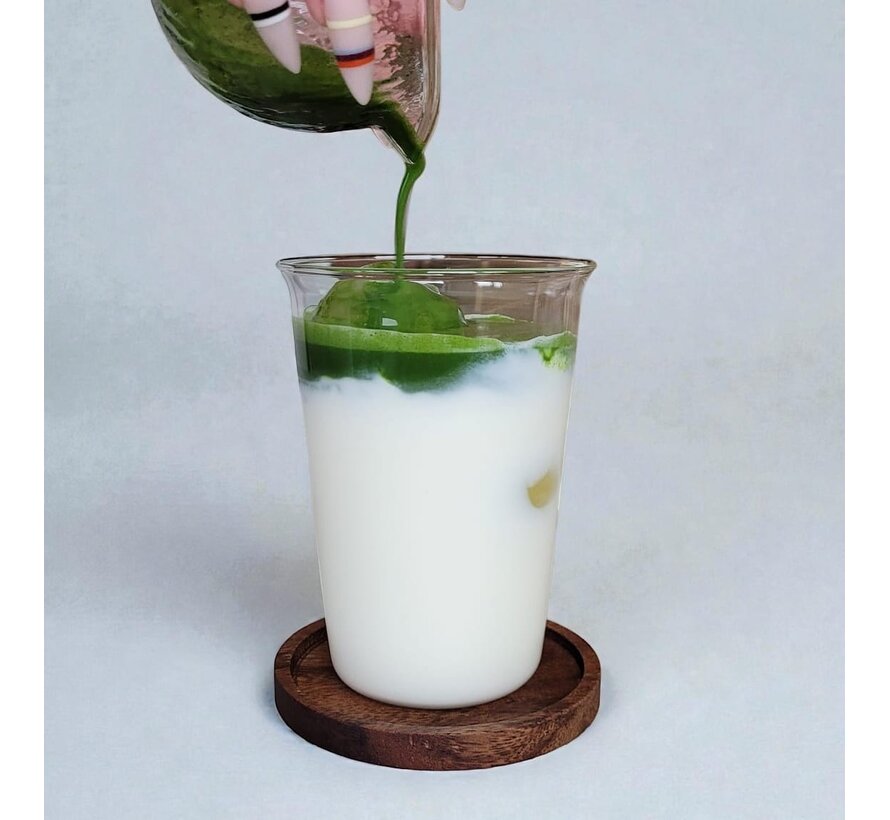

- For lattes: make sure the matcha is fully dissolved in the water and free of clumps before pouring it over the milk.

Standard recipe for pure matcha - 1 serving

1. Sift approximately 2 g of matcha powder (about 1–2 scoops with your bamboo spoon) into your matcha bowl.

2. Add approximately 60 ml of water at no more than 80°C.

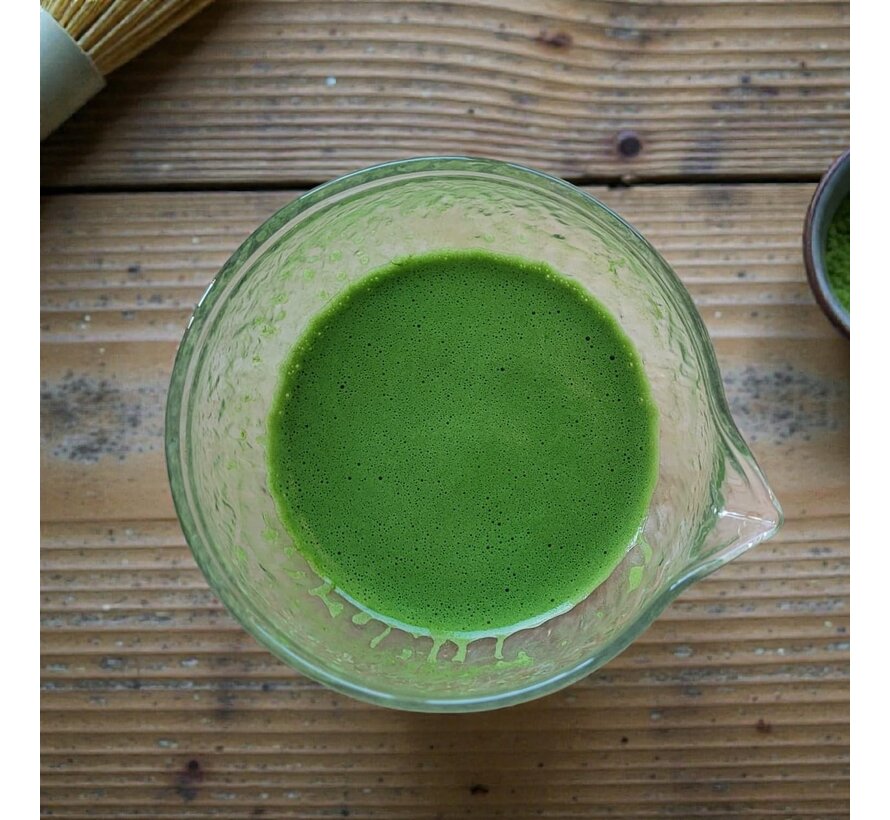

3. Whisk quickly in W or M motions until a creamy, fine foam forms. (Whisk fast but gently — foam comes from speed, not force. Avoid touching the bottom too much.)

4. Drink immediately.

Standard latte recipe

For a matcha latte, you usually use slightly more matcha powder (e.g. 3–4 g) and a bit less water (around 40 ml). Keep in mind: matcha contains a lot of caffeine. Follow the standard preparation above. In a separate glass, pour your milk of choice (about 150 ml) over ice cubes. Optionally add a sweetener to the milk first. Then pour the matcha foam from your bowl over the milk. Stir and enjoy!

Prefer it warm? First prepare the matcha foam using your bowl and whisk. Pour it into a cup (add sweetener if desired), then slowly add warm, optionally frothed milk — just like making a cappuccino.

The ratios we suggest are just that: suggestions. The best approach is to experiment and discover what you enjoy most. Tip: if your matcha tastes very bitter, try using slightly less powder next time (especially when drinking it pure).

Tools

We also offer a starter set, including all the tools, but without the teapowder. The tools are not only functional, but also aesthetically refined. The tools are made in Japan and feature a calm, neutral, and timeless design — loved by many, regardless of style or taste.